The Right Ingredient for the Right Product: Fats

This guest column was written by Ignacio Vargas, a food scientist and product strategist with more than 12 years of experience working on dairy products across various continents. He is currently working on the future of dairy as Head of Product for TurtleTree.

When we talk about alternative protein products, we tend to focus—as the category name suggests—on the protein source, giving much less thought to an equally important but oft-maligned macronutrient: fat.

As with finding the perfect protein source, food scientists like myself have come to learn that with fat there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Indeed, this may be even truer for fat than for protein, as fat not only significantly contributes to a product’s sensory characteristics (e.g. flavour and texture), but also to the cooking experience, nutritional value perceptions, and even the manufacturing process. Therefore, when developing a plant-based meat product for an APAC market, it is imperative to consider who your target consumer will be and what exactly they expect your product to deliver.

Texture

Especially in an Asian culinary context, texture is one of the most important food attributes according to consumer acceptance studies. Fat provides a mouth-coating richness and juiciness in meat, and the higher the fat content, the larger its impact on a product’s texture.

The point at which a fat melts is a result of its fatty acid composition. For conventional beef, that’s around 40°C. The melting points of acids commonly found in animal fats (oleic, palmitic, and stearic) vary widely, from 16°C to 63°C and 70°C, respectively. For plant-based products, the challenge lies in mastering how to mimic the fat melting temperature of conventional meat, using plants. If a plant-based product’s melting point is too low, it will start off juicy but then potentially expel all the fat during cooking, resulting in dry meat that falls far short of consumer expectations.

No single vegetable oil perfectly mimics animal fat melting points, but the closest contenders are coconut oil and cocoa butter, which have melting points of 25°C and 32-34°C. Not surprisingly, both ingredients are now found in popular plant-based products like the Beyond Burger.

In an Asian food context though, burgers are not king. Pork and chicken products are much more common, and their fat compositions vary widely. Conventional chicken is only 3.1 percent fat, whereas the figure for pork belly is a whopping 53 percent. Compellingly replicating these complex flavours in plant-based products requires finding fat ingredients that deliver a similar textural mouthfeel to what consumers have come to expect from their animal-based counterparts.

Flavour

Given that coconut oil and cocoa butter have some of the highest melting points among vegetable fats, they may seem like obvious choices for all manner of plant-based products. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, because producers also need to consider how the fat choice will impact the flavour of a product. “Nobody wants a burger that tastes of coconut,” says Dr. Max Jamilly of alt protein fat company Hoxton Farms, and products that fail to authentically match the meaty flavours buyers expect won’t earn repeat customers.

For this reason, some plant-based companies tend to use a combination of vegetable oils to find that magic mix. In the US, Mintel trends data shows that rapeseed, coconut, and sunflower combinations have become more prevalent, as well as newer oil sources like safflower oil, which has historically been used to substitute animal fat in conventional sausages. In Asia, brands like OmniMeat have sometimes opted for sesame oil, which they believe better complements local recipes and flavours.

Adding to the recipe complexity, vegetable oils are more prone to lipid oxidation, which can lead to undesirable off-flavours—it’s the same factor responsible for rancid flavors in animal meats, for instance—and potentially reduce a product’s shelf life. To minimise these effects, some companies resort to freezing or refrigerating the oils to ensure the quality of the finished products.

Nutrition

On the plus side, while vegetable oils’ high concentration of unsaturated fatty acids increases the risk of lipid oxidation, from a nutritional standpoint this is actually an advantage.

When we look at the “anatomy” of fat, so to speak, it is composed of carbon chain molecules called fatty acids. A fatty acid is considered “unsaturated” when a carbon of the chain shares two of its four bonds with another carbon, making a double bond. When we talk about omega- 3 or omega-6 fatty acids, this refers to unsaturated fatty acids having their first double bond in the third or sixth carbon of the molecule chain.

Vegetable oils are high in what are considered “good fats,” referring to unsaturated fatty acids (especially omega-3s), which have been associated with lowering the risks of heart attack and death from coronary heart disease. This is in contrast to saturated fats, which are most common in animal fat and which have been associated with an increase in “bad” cholesterol. The general recommendation from nutritionists is to reduce consumption of saturated fats and replace it with unsaturated fats (especially omega-3s).

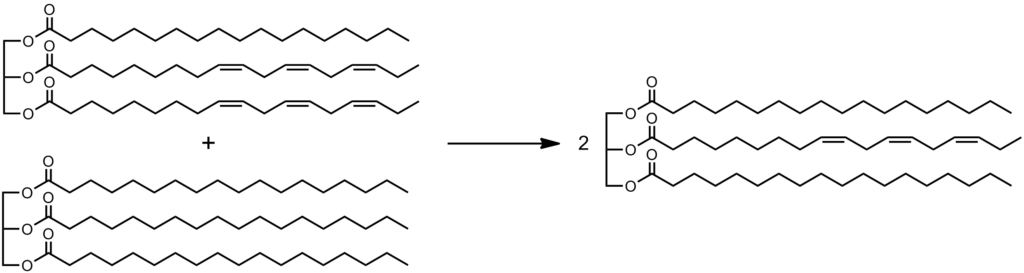

Comparison of Saturated and Unsaturated Fatty Acids

As you can see, while coconut oil has appealing attributes from a textural standpoint, flaxseed oil has a leg up when it comes to unsaturated fatty acid content, which makes it an ideal health-promoting fat option.

Beyond vegetable oils

With so many pros and cons to vegetable oil selection, one would think that by now food technologists would have taken steps to emphasise the attributes they want and minimise those they don’t. Indeed, many are doing just that.

One method, called hydrogenation, helped birth the creation of margarine by converting vegetable oil unsaturated fat to saturated fat, thus decreasing the product’s melting point and making it solid at room temperature like animal fats. On the downside, this conversion also generates trans-fatty acids, which are associated with increased risk of heart disease.

An alternate technological solution is interesterification, which consists of modifying the order of the fatty acids within the triacylglycerol (the molecule that “holds” three fatty acids). This method modifies an ingredient’s physical characteristics, such as its melting point, again making it closer to animal fat performance, but without the added burden of trans fats.

More recently, food flavour suppliers and startups have launched several new solutions, such as encapsulation, which basically covers the fat in a small capsule so that it is gradually released throughout cooking and consumption, thereby improving the texture and flavour of a product.

Perhaps most interestingly of all, companies specialising in cultivated fat—produced directly from animal fat cells—and innovative methods like precision fermentation are working to replicate conventional animal fat using novel ingredients tailor-made to achieve certain flavoural, textural, or nutritional attributes. These innovative methods are slowly ushering in an exciting new category of “hybrid” products that contain a rich combination of fats and other ingredients from plants, microbes, and animal cells, giving alternative protein producers a wider array of tools to satisfy their target audience.

Winning over the right consumers

68 percent of global consumers report that they are closely monitoring the type and amount of fat and oil in their packaged foods, according to Cargill’s Fattitudes report. In Asia, the Covid-19 pandemic has also increased consumer focus on a healthy diet and widened adoption and interest in plant-based foods. This presents an enormous opportunity for the alt protein industry to improve their products’ nutritional profile and win over a newly persuadable audience of curious consumers.

A deep understanding of Asia’s regional variations will be key here, as consumers in some countries, like Thailand, simply want to lower their fat intake across the board, whereas shoppers in Indonesia say they want to buy products that pack a stronger nutritional punch without compromising on taste. In some wealthier markets, like Singapore, consumption of healthy oils is a top priority—one reinforced by successful public awareness campaigns that have decreased saturated fat consumption through education. The smartest food producers know their target audience inside and out, and tailor their products to satisfy what that audience is craving.

35 years ago, the Washington Post published an article titled “Asian cooking, the secret is in using the right oil.” All these years later, its message is truer than ever: “Oil is not just a cooking medium; it flavors food and should be chosen carefully.”

Alternative protein producers would be well-advised to take a look at sobering consumer studies like the one recently conducted in Asia by multinational food company Kerry, which showed that nearly half of participants believe current plant-based meat products fall short on taste and texture compared to animal meat. Considering that taste and texture are two of the most important factors determining purchasing intent, plant-based meat producers that don’t think carefully about choosing the right fat for the right product risk leaving a lot of money on the table.

Ready to up your company’s ingredient game? Contact GFI APAC’s experts today to receive further product guidance, get connected to potential strategic partners, or simply chew the fat.